A simple invention transformed the manufacture of car number plates and built one of Britain’s most prosperous small businesses

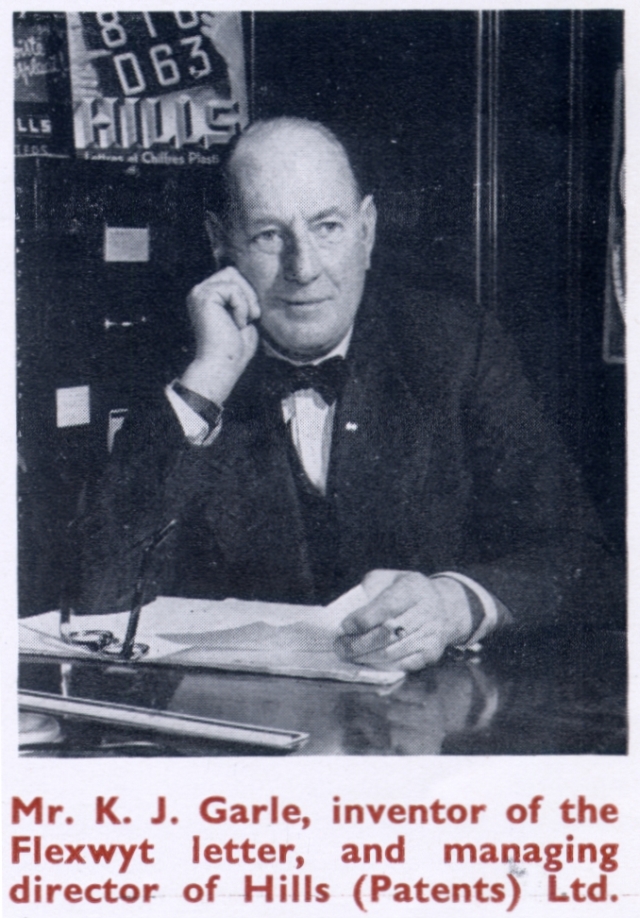

Poetic justice and a romantic public require a history of struggle behind successful business enterprises. The implication is that a golden spoon destroys incentive. That this is nonsense was proved by one of the country’s most successful small firms, HILLS (Patents) Ltd. Its founder, Mr Kenneth John Garle, never knew poverty and was never an employee. But was born with an inventive turn of mind, an abundance of energy and, no less important, an eager response to a challenge.

The first challenge came at the age of 19. He had passed through Clifton College and the City and Guilds Engineering College and was ripe, as his mother said, “For a lesson on how hard the world can be”. She persuaded his father to give him £50 to start a business. In those Edwardian days £50 went a long way and young Garle, in partnership with another youth took an office in Regent Street and launched into the still new and exciting motor car trade. The venture prospered and was soon exporting more cars than it sold at home. Its catalogue (a copy still exists) contained names that are still famous, like Rolls Royce, and many that are no more than landmarks in the history of motoring. By 1914 the little company was making an annual profit of £2,000.

The First World War put an end to these activities and in August 1914 Kenneth Garle took a commission in the Army. When the war ended, he found the motor trade much less attractive and looked around for another job. The opportunity arose through a bet. He wanted number plates for a car and grumbled at a delay of three days. Half-jokingly he said “I’ll bet I could make a pair in three hours”. In fulfilment of his wager, he had some loose aluminium letters cast for him with spigots on the back; he fastened these to a pierced metal plate and won his bet by completing a pair of number plates in fifteen minutes.

It was obvious that this idea of using separate letters and figures had great possibilities. It could replace the cumbersome casting process and speed up enormously the rate of delivery. The aluminium letters were shown to several garage proprietors whose reaction was very encouraging. Mr. Garle thereupon ordered a complete range of alphabet and numerals. At that time he was living in a mews flat over a garage. He rented the garage for £60 a year, turned it into a workshop and was soon working at the bench alongside his staff of three, producing a new type of number plate in quantities.

His friends were sceptical of this product as a potential money maker. Only a small section of the public was in the car owning class and of all motor accessories the number plate was the least likely to make repeat sales. In theory the critics were right; in practice they have been proven wrong. A highly durable product of modest price can be a financial success even when, as in this case, durability was a statutory requirement and the law was maddening in its interpretation of the term. The law relating to number plates was, for a time, a serious obstacle. The police, of course, had to interpret the law to the letter, and the registration and licensing provisions were precise: “that no letter or figure shall be capable of being detached from such a surface.”

Competitors were quick to make capital out of the legal weakness of the new form’s position. The chief constables in various counties were threatening the motorist with legal action and the whole weight of the law seemed to be invoked to stifle the new enterprise. Mr Garle reassured the trade by offering to stage a test case to clarify the situation. He had the Automobile Association and the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders (SMMT) on his side and they expressed their willingness to fight a test case for him if necessary. As it happened, he won his case without going to court, and secured amendment of the regulation as follows: “no letter or figure shall be capable of being detached from such surface, provided that it shall not be an infringement of these regulations if the letters or figures are made separately and either welded or firmly riveted onto such surface.”

All was plain sailing for HILLS (Patents) Ltd., till 1948. In that year the firm patented an entirely new type of letter made, not of metal, but of a white plastic material under the name of Flexwyt. These letters and figures were designed with a plastic spigot instead of a metal rivet for attaching to the backing plate. As the law specified riveting or welding, another amendment became necessary, and the regulation was revised so that “every letter or figure shall be indelibly inscribed or so attached to such surface that it cannot readily be detached therefrom.”

So a chance invention, while the century was still in its teens, was to take thirty years to win full legal recognition. Conservatism up to a point was a source of strength in the law, but carried to such lengths it might easily have daunted a less buoyant innovator than K. J. Garle.

There was no doubt about the quality of his innovation. The Flexwyt letters were so pliable that they could be bent or twisted in any way and yet always returned to their original shape. The spigot, was moulded in one piece with the letter, fitted into a hole pierced in the aluminium backing plate. An aluminium washer was attached and pressed home with a special tool. It was impossible to tear the letters away with the hands. The letters and digits were three dimensional and triangular in section so they were clearly visible from any angle. They remained white indefinitely and were claimed to be much more weather resistant than any other painted or embossed letter.

The motor trade at home and abroad welcomed the Flexwyt letter because it made them independent of the factory in meeting an order for number plates. Backing plates were stocked and a selection of letters and figures and a tool for punching holes to secure the washers were bought from Hills for a few pounds. This equipped Hills customers with components to supply a pair of number plates while the customer waited.

Flexwyt letters were patented throughout the world and were exported or made under license in 53 countries. Associated factories opened in France, Holland, Spain and South Africa. For their export business Hills (Patents) Ltd. studied motoring regulations in practically every country and adapted the size of letter accordingly. The Flexwyt letters prospered in export because of their light weight, ease of attachment by the user, and resistance to all climatic conditions. They were also used for street names and public signs as well as notices of all kinds.

For many purposes, notably Ministry of Transport signs in the UK, the embossed enamel plate was required, and at HILLS House, Chenies Mews, W.C.1, a large part of the production consisted of embossed work in a great variety of styles and sizes, from large direction indicators for main roads to small grave labels for cemeteries. As in the case of Flexwyt, the die-pressed plates were produced with great speed. A plate was made in an hour and despatched at once by post. The display industries were providing opportunities and this side of the business developed as a service to the trade rather than to the consumer.

In its machine branch, too, the firm was expanding. In addition to the neat little tool supplied to garages and dealers for fixing Flexwyt letters, which was manufactured in the Staines factory, a remarkable little metal cutting machine, the Hilshear was also produced. This machine filled a gap in the range of tools available to the artisan. Hand operated, power geared, and costing a fraction under £8, it performed tasks such as one would expect from much heavier and more expensive equipment. The Hilshear cut through 1/4in. steel, trim as fine a strip as 1/32in. from the edge of a metal sheet and even cut a 45º bevel along the edge of a piece of plate, preparing it for butt welding. The Government, the Army and other official departments were big customers for this tool and an increasing demand from overseas made it a priority production. The U.S.A., Canada and Switzerland, themselves being the leading tool designers and makers, were keen customers for the Hilshear.

In common with other small firms that introduced original products, HILLS (Patents) Ltd. trained its own operatives. It was a self-made enterprise in the fullest sense of the term; even its founder, self-employed from the start, had no direct experience of other firms, had to rely entirely upon his own skill and ideas. The two factories with more than 150 employees were his own creation. The products, the processes, and the system of administration, and even such details as the filing method were first-hand devices and expressions of a personality. Hills was viewed as a family business and, without overdoing the paternalism, it extended this family feeling to its employees. “Large organisations are the poorer”, Mr. Garle often said “because they have outgrown the dimensions of a family. But the small firm must also have the discipline that holds a family together. Only the large firm can afford to be inefficient; it is big enough to absorb mistakes which would leave the small enterprise no second chance”. He quoted with pride an overheard remark that “things seem to go on just as well when he is away” and considered it a compliment, not only to himself, but also to the loyalty of his staff and not least to his co-directors, Mr. C. B. Brudenell, among whose many activities was the care of the Staines factory and Mr. J. W. Mackenzie, in charge of finance and organisation.

Part of the vigilance which the head of the family contributed to this particular family business was a flair for opportunity which kept machines constantly busy and crafts flexible. The war provided a good example. Mr. Garle stumbled one day over a metal object in a field at Woolwich Arsenal. It turned out to be a rusty and discarded Ward lathe. New lathes were unobtainable and he jumped at the opportunity to buy this one for a few shillings. After a fortnight’s overhaul, it started to produce aircraft parts to a 2,000th of an inch precision, six days and six nights a week till the end of the war-and that for Woolwich Arsenal!